Note: There was another John Edmonds living in Fayette County in 1850, the son of Nathan and Eleanor Edmonds. He was a little older, having been born in about 1835. Although apparently missing from the 1860 census, he shows up again in 1870 and later, having married Manerva Kilgore in 1866. Edmonds researchers have often easily gotten the two John Edmonds confused.

Given that our John Edmonds “disappeared” in the 1860s, one must consider the possibility that he was a Civil War casualty.

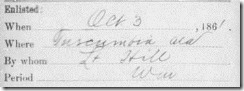

There was a John Edmonds who enlisted in Company A, 26th Alabama Infantry (O’Neal’s)

October 3, 1861, in Tuscumbia, Alabama. Tuscumbia, Colbert County, is a few counties away from Fayette County where John Edmonds lived. However, histories of the 26th Alabama Infantry indicate that “men were recruited from Fayette, Marion, Tuscaloosa, Walker, and Winston counties.” This seems like our John Edmonds, but we can’t be sure yet, especially since the other John Edmonds was also from the area. [Extensive Civil War records can be found at fold3.com, formerly footnote.com.]

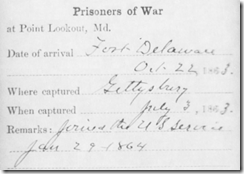

October 3, 1861, in Tuscumbia, Alabama. Tuscumbia, Colbert County, is a few counties away from Fayette County where John Edmonds lived. However, histories of the 26th Alabama Infantry indicate that “men were recruited from Fayette, Marion, Tuscaloosa, Walker, and Winston counties.” This seems like our John Edmonds, but we can’t be sure yet, especially since the other John Edmonds was also from the area. [Extensive Civil War records can be found at fold3.com, formerly footnote.com.] The 26th Alabama Infantry fought in the Battle of Gettysburg (July 1-3, 1863) and suffered losses of 7 killed, 58 wounded, and 65 missing. John Edmonds’ Confederate records show him captured at Gettysburg and a Prisoner of War at Point Lookout, Maryland. They also mention that he “joined the U.S. Service”.

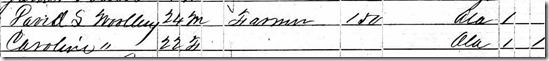

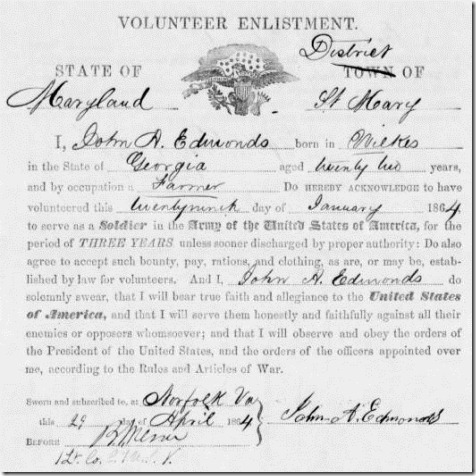

The 26th Alabama Infantry fought in the Battle of Gettysburg (July 1-3, 1863) and suffered losses of 7 killed, 58 wounded, and 65 missing. John Edmonds’ Confederate records show him captured at Gettysburg and a Prisoner of War at Point Lookout, Maryland. They also mention that he “joined the U.S. Service”. Now it’s time to look in the Union Civil War records. Found: John A Edmonds who enlisted January 29, 1864 at Point Lookout, Maryland, in the Company D, 1st Regiment US Volunteer Infantry. These Union records show that John A Edmonds born in Wilkes County, Georgia, was 22 years old at the time, and was a farmer. This fits our John A Edmonds exactly. He is also listed as 5’ 10” tall, light complexion, hazel eyes, and sandy hair.

The 1st US Volunteer Infantry was made up almost entirely of captured Confederate soldiers who were given the opportunity to enlist for the Union in order to get out of Prisoner of War camps. These soldiers were dubbed “Galvanized Yankees”. However, they weren’t sent to fight against the South -- they couldn’t be trusted for that. Instead, they were sent to guard forts in the Dakota Territory.

John A Edmonds’ records show that he was promoted from Private to Corporal on July 1, 1864. On September 11, 1865, he was listed as “deserted” from Fort Rice, Dakota Territory.

John A Edmonds’ records show that he was promoted from Private to Corporal on July 1, 1864. On September 11, 1865, he was listed as “deserted” from Fort Rice, Dakota Territory. John A Edmonds wasn’t alone in his desertion.

Many deserted—as men chose home or the gold fields over another winter of death at Fort Rice. Eleven percent of the command had died the previous winter, and all who survived still suffered from scurvy's lingering effects.Desertion might not have been such a bad choice. John A Edmonds and other Galvanized Yankees weren’t exactly welcome back in their home states in the South. Likewise, they didn’t have much in the way of ties to the North. The West may have looked like a good opportunity to start a new life.

Like volunteer troops elsewhere, the First U.S. Volunteers believed that they had earned the right to go home—especially since their former prison comrades had been released in the spring. The ex-prisoners of war had requested through channels to be mustered out when news of Appomattox reached the Upper Missouri, only to be turned down by the War Department.

[Prologue Magazine; Winter 2005, Vol. 37, No. 4; Trading Gray for Blue

Ex-Confederates Hold the Upper Missouri for the Union; http://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2005/winter/galvanized.html]

I would love to find John A Edmonds in records in California or elsewhere in the West after 1865. These findings may not take me to John Edmonds’ eventual rest, but they do add a few more exciting years on to his history.